|

|

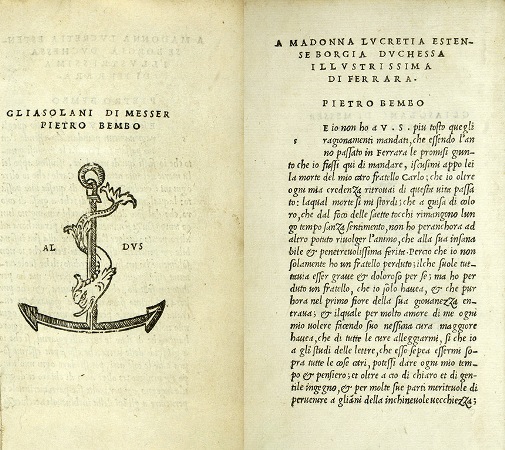

Private collection Gli Asolani by Pietro Bembo, 1505, dedicated to Lucrezia Borgia, Duchess of Ferrara |

500th Anniversary of the Aldine Press

| By Roderick Conway Morris | VENICE 3 September 1994 |

Compact, portable, capable of storing tens of thousands of words, with random access and requiring no power - the book, as Arthur C. Clarke has observed - is an information tool of the future as well as the past.

That the modern book, as we would recognize it today, was born so soon after the invention of movable metal type in the mid- 15th century, was principally the work of one man - Aldo Manuzio, founder of the celebrated Aldine Press in Venice 500 years ago this year.

To mark the anniversary, the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice's national library, has staged an attractive and thought-provoking exhibition of more than 150 Aldine books and related manuscripts, 'Aldo Manuzio and the Venetian Milieu, 1494-1515,' which runs until Sept. 15. The setting is the first-floor vestibule and main hall of Sansovino's library, opposite the Doge's Palace, not usually open to the public.

Manuzio was born near Rome in about 1450, at about the same time as the dawn of printing, and led the life of a wandering scholar and teacher until, in his 40s, he launched himself on a new career as a publisher. Venice had already established itself as the superpower of early publishing.

The Venetian government was quick to appreciate the possibilities of the new technology and the favorable conditions the city offered, from a skilled work force and an abundant local supply of paper to access to one of the largest and most cosmopolitan markets in the world.

For Manuzio, Venice had an added attraction. It was his primary ambition to publish Greek classics and, after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, the city had become the refuge of so many Greek scholars, bearing thousands of manuscripts, that it had been dubbed 'almost another Byzantium.'

Manuzio's program to publish books in ancient Greek may seem rarified. But the flair and imagination he brought to the enterprise made him rapidly the most influential publisher of that, or possibly any other, age.

As a glance at any of his productions confirms, for him a book was a book, a new phenomenon that demanded a distinct form of its own. Thus, when many other backward- looking printers were issuing books that resembled manuscripts, Manuzio squarely addressed the newly emerging secular 'reading public' who wanted to read for education and edification, certainly, but also for pleasure.

To this end he created the octavo format, handy, portable and pocket-size. His texts were exceptionally clear and crisp, with wide margins and, to increase the ease of reading these smaller-format books, he invented what he called cursive type, better known as italic. He pioneered page numbering to aid rapid reference, and though his books ushered in new standards of care, he initiated the errata page to correct fugitive errors. Even the simple, elegant and practical bindings set the measure for centuries.

While he never lost sight of his central goal of publishing Greek books, he brought out numerous others in Latin and Italian, and even Hebrew, which achieved for him additional publishing firsts, including war memoirs, an instant medical book on gonorrhea, then ravaging Italy, and a modern-style travel book on the Caucasus. With Erasmus's 'Adages' - a tome of Greek and Latin quotations - he created the first best seller. To produce it, he suspended the printing of other titles, obliging the Dutch humanist, then in Venice, to write against a deadline, printing as the copy came in.

His capacity for work was astonishing. He edited, set and printed almost the entire known works of Aristotle - nearly 3,800 pages - within three years. His high-pressure style of production was clearly not always understood by his contemporaries, hence the sign outside his printshop, which read:

'Whoever you are, Aldo earnestly begs you to state your business in the fewest possible words and be gone, unless, like Hercules to weary Atlas, you would lend a helping hand. There will always be enough work for you, and all who come this way.'

The famous logo of the Aldine Press - a dolphin entwined with an anchor, denoting speed combined with reliability - was in due course imitated by other publishers as the ultimate symbol of publishing quality (often with scant justification).

Needless to say, Manuzio's books were extensively counterfeited. He helpfully warned his customers that you could literally smell such substandard fakes, as he used only the best paper and ink, a boast confirmed by the books in the Venice exhibition.

A perfectionist to the last, in 1513 he declared that 'I have never been satisfied with any book I have published.' But, in reality, by the time he died two years later, through his unique vision and superhuman energy, he had not only guaranteed the survival and diffusion of ancient Greek literature, but also set standards of production in publishing that have yet to be surpassed.

First published: International Herald Tribune

© Roderick Conway Morris 1975-2024