|

The original photojournalist

| By Roderick Conway Morris |

LONDON 1 April 1998 |

|

John Phillips was not only one of the best photojournalists of the century, but the first to have this style of label attached to him. As he recalls in this highly informative, acute and enjoyable feast of a book, illustrated with over 200 of his superb photographs: '… the first time the words photographer and reporter were linked together in print was in December 1939. I had just completed a story on Canada going to war. As usual I had supplied the Life writer Hubert Kay with copious captions and research along with the pictures. As I was the magazine's 'Photographer of the Week', Kay wrote a box about me. ''I've coined a term for you,' he said, 'I've called you a reporter photographer'.' Kay the writer had naturally put the words ahead of the pictures, but with use the term became photo-reporter, and eventually, photojournalist.'

Phillips was born in Algeria in 1914 of an American mother and decidedly eccentric Welsh father, an amateur photographer - who 'took his hobby far more seriously, required far more equipment and far more space than any of the professionals I got to know in later years' - but he himself actually learned the mysteries of the trade as a schoolboy weekend and holiday assistant to M. Pansier of Paris Photo, a tiny shop below the family's apartment in Nice, where they lived for some time after leaving Algeria.

At 22 Phillips was taken on in London by the then about to be launched Life magazine. He set off on his first assignment, to get 'local colour' at Edward VIII's opening of Parliament, with the editor's exhortation: 'Be original. That's what Life expects.' Unfortunately, the aspiring photoreporter's 'numbing shyness' reduced him to taking a series of people's backs - 44 in all. 'A peculiar look came over the editor's face as he flicked through my pictures. Putting down the last print, he said, 'It's either of two things and I don't think you're a half-wit. I asked for pictures that were different and I sure got them.'

Happily, this proved not the end but the beginning of a brilliant career, that took Phillips all over Europe, North and South America and the Middle East. He was often one of the few, sometimes the only, foreign photographer or reporter to record great events - and it is one of the many revelations of the book finally to get 'the story behind the story' of many of his famous pictures, such as those of Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at the Teheran Conference, and of Tito directing operations from his mountain cave.

Clearly a brave man, but one who regarded, for example, being in the front line with Tito's partisans or the battle for Jerusalem in 1948 as all part of the job, Phillips was also endowed with that streak of native cunning that makes for the successful journalist. Having managed secretly to take pictures of Hitler's enthusiastically-received occupation of Vienna in 1938, Phillips set off on the night train to smuggle them out of Austria and found that he was sharing a compartment with a prominent Nazi. Knowing that only his own luggage would be thoroughly searched by the Stormtroopers at the border, he slipped his films into the Nazi's greatcoat pocket, retrieving them when the Nazi fell asleep after the train had rumbled across the border.

But while Phillips would go to almost any lengths to get his story and the evidence back to base, the overwhelming impression is of a man of sensitivity, integrity and decency. An expert in the subtle approach and at blending in - arts that enabled him to capture many of his most telling images, he was unsurprisingly bemused by today's paparazzi: 'In my time we were expected to dress for the occasion: black tie for most ceremonies, white tie for weddings, and a grey top hat for the Derby. Today's photojournalists look like big game hunters stalking their quarry with their powerful tele-lenses and loose-fitting bush jackets with large pockets.'

It is a shame that Phillips, who died in 1996, did not live to see the publication of Free Spirit, or to continue his account of his no less interesting career after he went freelance. But he has left behind him a classic memoir by one of the finest observers of his age.

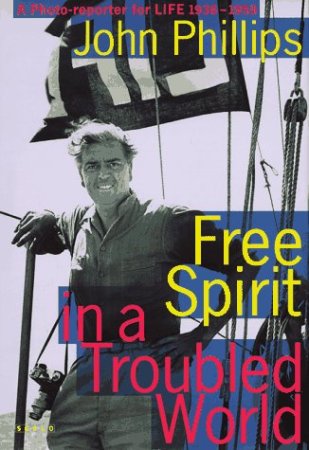

FREE SPIRIT IN A TROUBLED WORLD

by John Phillips

Zurich 1996

First published: Traveller

© Roderick Conway Morris 1975-2024